When you start telling people you’re leaving the country, they have a lot of questions. Some say they want to leave too but the thought is overwhelming. The first mental hurdle is they can’t imagine getting rid of all their stuff.

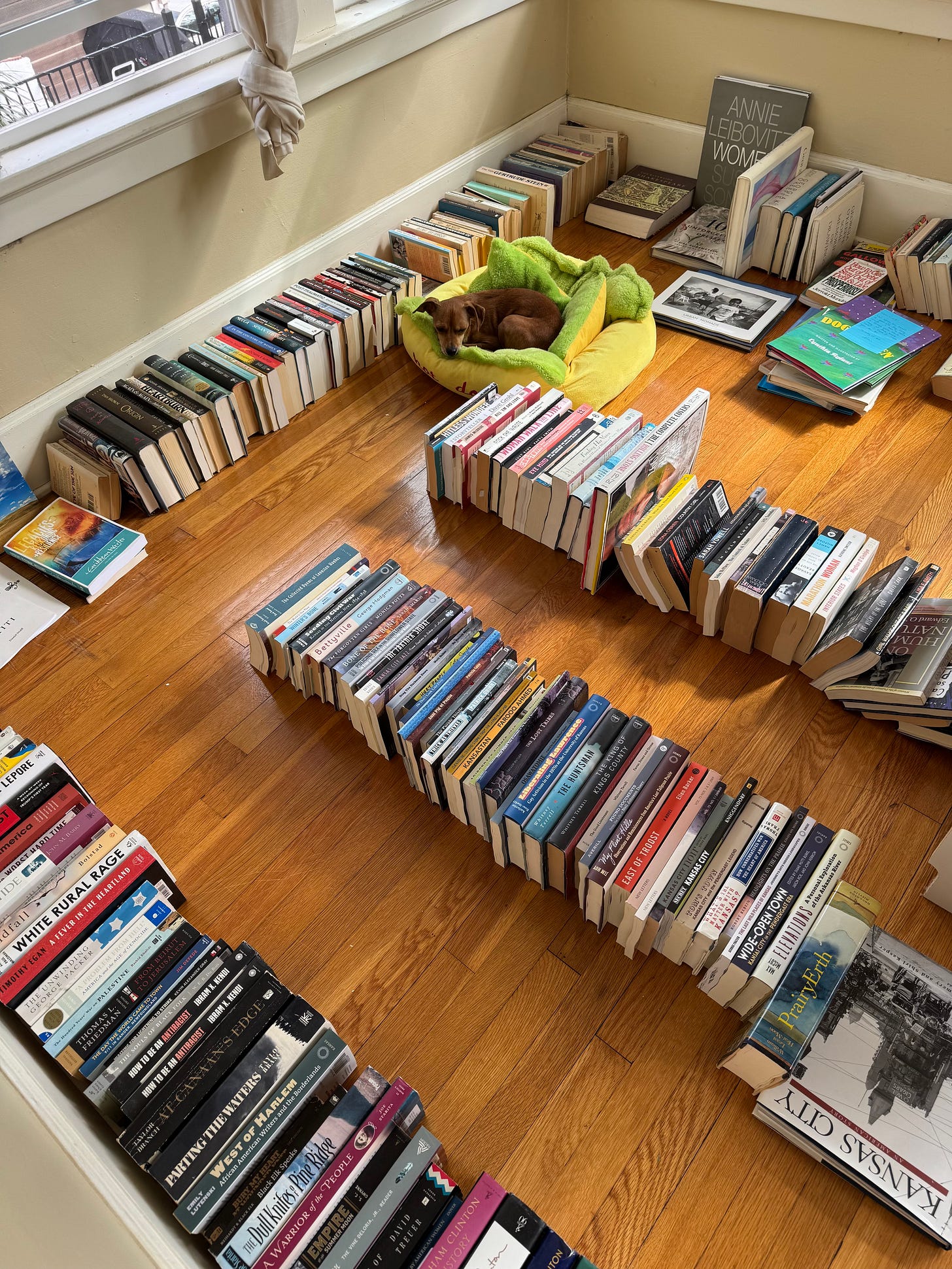

Here’s how you do that.

First, don’t even think about the vinyl. You haven’t listened to it for years anyway. And the collection’s nothing special, just three feet of classics from the ‘70s and ‘80s, a few childhood favorites — Disney’s “The Jungle Book” (1967), Pete Seeger’s “Children’s Concert at Town Hall” (1963) — and the Latin jazz, Broadway musical soundtracks and Record of the Month Club oddities inherited from your Mid-Century Modern grandfather. Selling it all would be an entirely different project. When your sister offers to haul it away to distribute among her audiophile friends, take her up on it. You have it all on your phone now anyway.

Start with the smallest things you know you want to keep. The small bowls you made in high school pottery classes, the ones that remained unbroken through moves across the country to college and grad school, in and out of apartments with exes and finally to the house you where you and your wife have lived for decades but have just sold. Pack these pieces carefully surrounded by wads of newspaper in boxes small and light enough to ship later as inexpensively as possible on DHL (DHL is never inexpensive).

Move on to harder stuff. Paintings by graduates of the local art school, once rising stars whose work you bought when you were flush from your first good-paying job, at First Friday studio tours just as everyone was rediscovering the city’s abandoned stockyards district. The art scene later migrated and began reviving other forgotten neighborhoods, while your artists left town. When current gallery owners aren’t interested, give these paintings to friends who remember those days.

Make arrangements for the living things. Plants you managed to keep alive as you also grew. Give these to friends who watched you turn 30, then 40, then 50, then 60, and are willing to accept this responsibility.

Don’t cry. You haven’t cried in a long time anyway, armored up as you’ve been against what’s happening in the country. You know enough history to recognize it; it’s not even hard to see. You just have to be willing to accept that it’s happening in America.

Open dusty plastic totes in the basement. Go through folders of paper simultaneously musty and dry. Google how long you really have to keep bank statements and tax returns. Read letters from friends you now email and others you lost track of decades ago; google, unsuccessfully, to try to find the lost ones. Appreciate a lifetime’s worth of birthday cards from parents and long-gone grandparents. Open all the envelopes from One-Hour Photo, realize how many of these pictures are not of people but clichéd and generic vacation scenery. Skim college papers, the ones that earned compliments from beloved professors, and remember how confident you were back then. Fill six brown paper lawn bags and take them to a professional shredder. The cost of securely destroying this documentation of your life is $60. Completely reasonable.

On a dreary January weekend, go through boxes of cassette tapes, also in the basement. Because you are an obsessive recycler, separate the tapes from their plastic cases and paper track lists, remembering the girlfriend who was a DJ at the gay bar and made you mixtapes crafted so song titles created narratives (Carla Bonoff’s “Personally” followed by Prince’s “I Wanna Be Your Lover” followed by Kool & the Gang’s “Get Down On It” and Michael Jackson’s “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” and so on). Marvel at how tedious it used to be to make a mixtape.

Watch, horrified, as friends in Los Angeles evacuate from fires that reduce their homes to ash. Read the Facebook posts they wrote while they were in shock. They lost everything in a matter of hours. You’ve already spent a lot of time thinking about people throughout history who’ve left their homes with nothing. Be grateful you can get rid of stuff on your own terms.

Once you start talking about a moving sale, friends will offer to buy things they’ve fallen in love with over years of dinners at your house and summer afternoons on the deck. You never knew they even noticed this stuff. Sell it to them!

For the moving sale, price almost all of your possessions at one or two dollars. Shake off the discomfort of strangers flowing through your house. After all, the house isn’t really yours anymore. You already sold it.

You’re doing something other people tell you they wish they could do. Some say it must be liberating, and it has been.

After the moving sale, in the last days before you leave town, sleep on an air mattress with only a handful of suitcases. Clothes and small things you’re taking to your new home across the ocean.

Wake up one morning with itchy, nickle-sized welts covering one leg and the opposite arm, thinking you were attacked in the night by an especially aggressive insect. A week later, wake up at your sister’s house in a different city with more welts elsewhere. Realize, for the first time in your life, you’ve broken out with hives. Apparently you’ve been having emotions about all of this after all. Take some Benadryl.

Moira Donegan and Adrian Daub, at In Bed with the Right, have been recounting 1933 month by month, drawing largely from contemporaneous diaries. I couldn't help but imagine this piece being read by a future Moira and Adrian (with Adrian explaining what cassette tapes were), as they tried to give granular, human realism to the events of history books describing 2025. I'm gutted, of course.

So well written and spot on with the “yeah, that too!” thing: mix tapes, real photos and the ability to reach a long way away. Love to you and Lorraine. Go get it.